My story begins on July 16, 1982. The first words from the obstetrician to my mother were “congratulations, it’s a boy and we have to take him immediately into emergency surgery to surgically close his back.” I was diagnosed with Myelomeningocele with an L2 lesion on my lumbar spine, minor hydrocephalus, and had a VP shunt placed. In 1982, an amniocentesis was not recommended and ultrasounds were not widely used…The physician’s prognosis at that time was “your son will be retarded (Note: I use this word not to offend, but rather, to illustrate the medical terminology used by medical professionals in the 1980s), likely won’t finish high school, and will never be independent.” It became clearer, as I grew, that none of those predictions would come true.

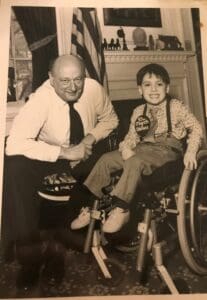

As a young boy growing up in the 1980s, in government subsidized housing, with a single mother in Queens, New York- an accessible pre-school education was out of the question. A steady diet of books, parks, and the Hall of Science in Queens were my early educational intervention. This is where my passion for science and nature arose.

Approaching kindergarten, the New York City public school system was determined to keep me out, as they were not equipped to support a student with a significant disability. One of the only options available was to be enrolled at the Henry Viscardi School for students with severe disabilities; this was no simple task either. We lived in a very low resource area with little to no access to early education intervention. Because I had no history of preschool, Henry Viscardi was skeptical of enrolling me until they administered an IQ test. Once the results came back, they welcomed me there and I thrived. I became one of their top students. Despite my success at Henry Viscardi, I became more vocal about joining my sister in a mainstream public school while in the 3rd grade. After tenacious advocacy and dogged persistence from my mother (mostly) and me, we convinced the school system in Long Beach, New York, to enroll me in their elementary school and to build a permanent ramp to access the main entrance. The transition to a mainstream public school in 4th grade was not a smooth one. Between advocating for my needs as a student with a disability and managing a significantly more rigorous academic curriculum, I spent many days during that first year tired, frustrated, and questioning my decision to be mainstreamed. There were assignments missed and tests failed. It was extremely challenging, but it was all worth it in the end.

As I adjusted to the immense changes and challenges both academically and socially, and found adaptive strategies, I slowly began to see improvements in my grades and social life. In many ways, I was a typical kid: playing video games, watched wrestling and movies, and, went to concerts with friends as I got older. I played wheelchair baseball, persuaded an instructor to adapt his judo class so I could participate, and fell in love with wheelchair tennis. Participating in sports was not always a given because my new hometown of Long Beach would initially not allow me to play tennis on their public courts because they claimed that my wheelchair tires would damage them. I decided to take my case to the Long Beach City Hall to advocate for equal access to the courts and invited the local news to cover it. After appealing to City Hall, I was granted access and tennis lessons. I also played on the weekends in Queens where the USTA held a free wheelchair tennis clinic. As I improved, I would spend some summers as a camp counselor who taught tennis to all children. I spent others summers, from age 14, working in various jobs, such as a ticket taker on the beach, as an administrative assistant in City Hall, and for the Long Beach City school system. It was in these jobs where I honed my advocacy skills, executive functioning, planning, and money management skills. Most kids in their teens probably wouldn’t want to spend their summer vacations working, but it’s where I cut my teeth earning my own money and learned valuable lessons about working within teams, time management, and normalizing having people with disabilities be visible in the workplace.

During junior and senior year in high school, I took honors and advanced placement level courses, was involved in student government, managed A/V for high school theater productions, played trombone in the band, and was still actively playing wheelchair tennis. Going to college was certainly well within reach. During this time, my mother spoke with a neighbor about how I was applying for college, and the neighbor said “Oh, you don’t think he’ll be able to go to college, do you?”, in spite of the fact that I had highly competitive grades and SAT scores, and was an overall well-rounded student. My mother was stunned; the thought that I wouldn’t go to college had never occurred to her. Undeterred by ignorant comments, I pressed on with applying to colleges with my family’s support. I was accepted into 7 of the 8 colleges and universities to which I applied, and in the early spring of 2000, I made the decision to enroll at the State University of New York (SUNY) at New Paltz. Before I received my acceptance I had applied for the Spina Bifida Association of America’s academic scholarship. We received a thin envelope from the SBA in the mail, and assuming that a thin envelope meant a rejection letter my mother threw the envelope in the trash! Fortunately, I persuaded her to fish the envelope out of the trash and check the letter. Lo and behold, I received a very generous $20,000 over 4 years to pay for my education! The scholarship was crucial—allowing me to graduate debt free.

My experiences at SUNY New Paltz will not be forgotten. I was about 3 hours from home, which was just far enough for me to learn to navigate college, but close enough that I could drive home for a long weekend if necessary. I was very active in the campus community, volunteered my time to renovate homes with Habitat for Humanity, participated in Biology club, was a part of the student Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), was a tour guide for incoming students, an official student peer mentor to incoming students with disabilities, and part of a committee of students with disabilities which advised the university president on improving accessibility on campus. I also made time to have fun, a lot of fun, but I never allowed it to get in the way of my studies. My time at SUNY New Paltz taught me to be an advocate for myself, whether it concerned accessing the fitness area, clearing my class route of snow and ice during the winter months, or changing the location of inaccessible classes. I navigated advocacy in a way that I hadn’t fully done in the past—as an independent adult. I graduated in 4 years with a degree in psychology and a minor in computer science. I still look back on that time fondly and feel grateful that I studied what I loved, forged relationships that have lasted close to 20 years, and was an advocate for students with disabilities on campus.

My older sister attended and graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC Chapel Hill) in 2003, a year before I completed my degree, and my mother and stepfather decided to take a risk and move down to NC that same year. Although I was hesitant to leave the only state and tight-knit social circles I’d ever known, I reluctantly moved down to the Research Triangle area of North Carolina hoping to find a new home and community that would afford me the opportunity to live fully as an independent adult with Spina Bifida. After briefly moving into my parents’ house in May 2004, I quickly found my own apartment and began living independently.

Realizing that although my parents were incredibly supportive in so many ways, they did not have the means to help pay the rent and bills, I quickly put together a resume and drove to any business related to research, science, and healthcare to inquire about open positions. This was 2004, and hardly any platforms existed to apply for jobs online. Fortunately, there was a cytogenetics laboratory across the street from my apartment that was hiring Karyotypers. I had no idea what a Karyotyper did, but they were willing to take a chance on a young, ambitious, enthusiastic recent college graduate, and I got the job. I made it my mission to study the shapes, patterns, and abnormalities of chromosomes, and became one of their top employees. Over the next year, I was dreaming up what I wanted out of a career. I applied and was accepted to a masters of social work program at UNC Chapel Hill. I quickly realized that the program was not a good fit for me and made one of the most difficult decisions to drop out of the program. Unemployed, overwhelmed, and unsure of my career path, I became curious about a mindfulness-based meditation program being offered at Duke Integrative Medicine. Little did I know that going through this program would change my life in many ways.

Equipped with a new and healthy way of coping with stress and anxiety about my future as an adult with a disability, I set out to embark on a career in clinical research. Fortunately, the Research Triangle Park area is a hotbed for those with aspirations of a career in the clinical and public health research field. While I had support from family and friends, I did not have a mentor or peer, particularly one with a disability, who could be a source of guidance and inspiration along the way. What I did have was the ability to be resilient, plan for the future, manage my bills and finances mixed with ambition. I held a few entry and mid-level positions in clinical data management, quality control and assurance, and clinical site start up and management for several years.

At the same time, I continued my meditation practice. The more I practiced, the more I realized the physical and mental health benefits of it. With a bent toward science and research, I spoke with any researcher in the area who was studying the medical and health benefits of a mindfulness practice. Things came full circle when I found a researcher affiliated with Duke Integrative Medicine who was looking to hire a clinical research coordinator. I got the job, and this time wasn’t a participant in their program, but research specialist interested in advancing the science and knowledge around a mindfulness meditation practice. The practice, benefits, opportunities, and relationships established with mindfulness meditation have been many and is the gift that keeps on giving. It was this experience, along with a desire to further advance my career, that spurred me to re-consider graduate school, this time in public health.

Along my career journey, I was fortunate to have had a supervisor who took an interest in my career as well as my personal growth. She knew that I did not have a lot of money, but did have a good job, good credit, and was independent and responsible. She happened to come across and share with me an advertisement for an organization that provides affordable housing in Orange County, NC, which was where I was renting an apartment at the time. I had been seriously considering homeownership, but with a modest salary and few wheelchair-accessible options, this seemed like a dream deferred. However, I found the perfect ground floor condominium through the affordable housing program in a village that was wheel-able to a grocery store, restaurants, a gym, and shops. My mother and stepfather assisted with gathering information. It almost seemed too good to be true, but in 2010, I became a first-time homeowner at twenty-seven. While it came with plenty of responsibilities and the occasional maintenance issue, it allowed me to live my life as an independent adult with a disability on my own terms.

As I had taken several steps to establish myself including an education, a good job, and a home, there was one area that needed my attention—finding someone to spend my life with. I had been on a few dates mostly through online dating, but most of the time they flamed out after only a date or two. I had mostly given up on dating when I bought my condo. I’ll freely admit that for most of my adult life I was opposed to the idea of dating, let alone marrying someone with a disability. This was mostly because I was still figuring out how to properly care for myself and wasn’t confident that I could manage the care of someone else with a disability; maybe some of it was hubris. Fortunately, I came to my senses and realized that there were many independent people living with disabilities and opened my mind to this possibility. I met my wife Stephanie for the first time over lunch, after mutual friends connected us. Neither of us had the expectation of a first date. We were two educated, successful, ambitious people with disabilities who were looking to connect with others. We had so much to discuss that our lunch lasted for four hours and the restaurant staff asked if we wanted to just go ahead and stay for dinner. After that first lunch, we spent almost every weekend together and it wasn’t long before we were engaged and then married a year and a half later. We’ve been married for close to a decade. We’re both fierce advocates for our respective disabilities and each other, we love to travel and find the most accessible and fun places to explore at each destination, we’re doting uncle and aunt to 6 nieces and nephews, and provide support to our families in equal measure that they support us. We live independently in an accessible home, and in 2020, found a ground floor condominium that we’ve transformed into a rental property to provide accessible, affordable housing to any person, regardless of their mobility. We continue to find ways to support each other throughout a very challenging pandemic.

As I was reconsidering graduate school, I set my sights high by applying to UNC Chapel Hill, the top ranked public health school in the country. Although my GPA and GRE scores were competitive and I had significant experience in clinical research, I knew that being admitted would still be a tall task. I decided to go to the program open house so that I could meet with the faculty and staff and tell them about myself personally, rather than being a faceless applicant. Although I was waitlisted at first, I eventually gained admission into the program. In 2015, after 2 years of intensive study and team projects, I completed a Masters of Public Health degree. My wife, family, and friends were immensely supportive along the way. My MPH has led to a successful and fulfilling career as a clinical research manager in the medical field.

My advice to people with Spina Bifida and other disabilities in all stages of life is to keep finding ways to defy expectations, push boundaries, and question the status quo. Become an advocate and a leader, even in small ways. Envision what you want your life to be, whatever it is, and determine how to make it happen while accepting help if it’s offered to you. Take calculated risks—they can lead to an invaluable education, fulfilling career, a loving marriage, or whatever else you can dream up.

Recent